Did the Altar Stone originally stand upright or lie flat?

by František Hájek

One of the mysteries of Stonehenge is stone 80, known as the Altar Stone. It is unique within the monument. It has a distinct slab-like shape, unlike the other stones, and is the only one of its kind—made from a different type of stone than the two main types used in the monument: sarsen and bluestone. Its origin is now being re-examined. Instead of the previously assumed source in relatively nearby Wales, a much more distant origin in northern Scotland is now being considered. Another mystery still not fully resolved is its original position and, most importantly, its purpose.

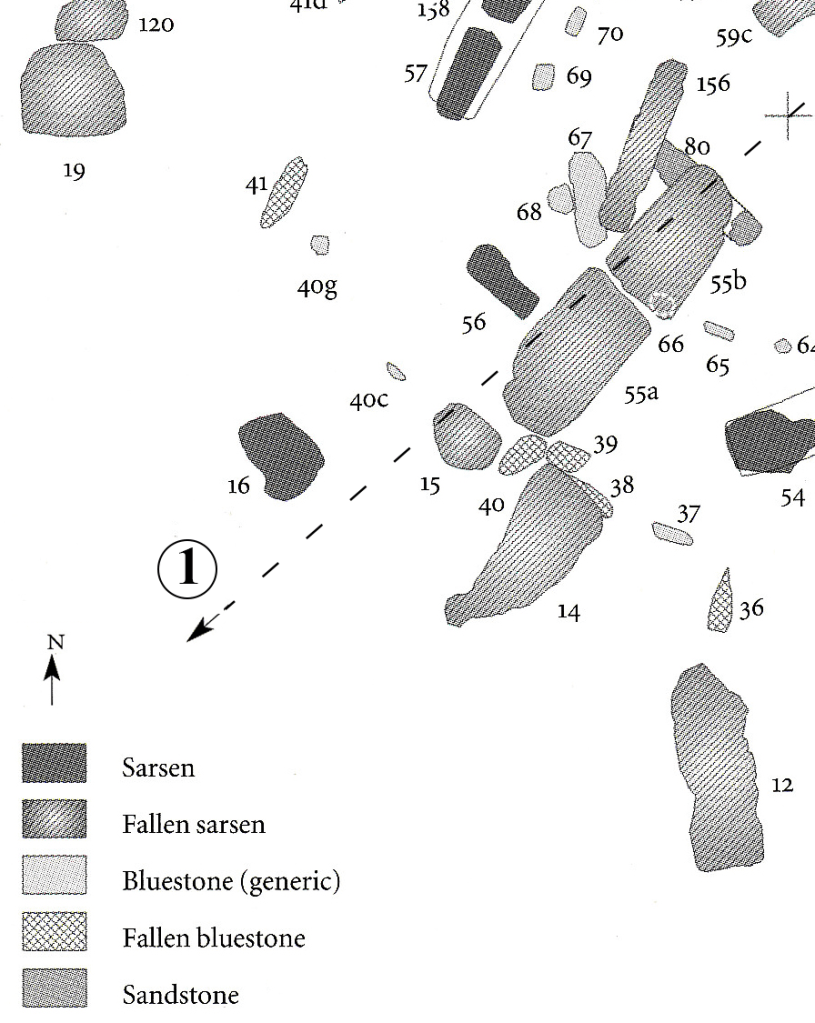

The Altar Stone currently lies flat in the southwest portion of the central interior space of the monument, formed by the five trilithons (Fig. 1). It has been referred to as the Altar Stone since the 17th century.

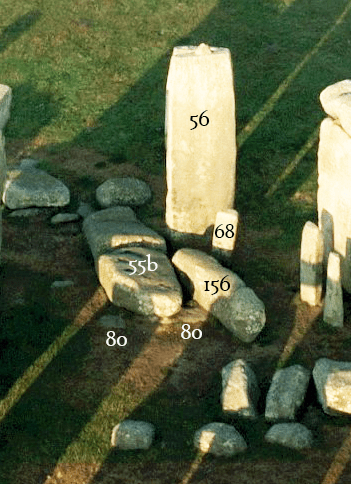

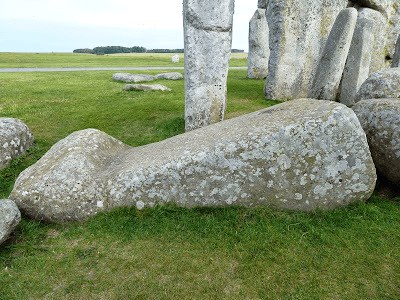

Today, it is barely visible—only a portion of its top surface can be seen [1, 2, 3], as it is almost completely embedded in the surrounding earth and locally covered by fallen elements of the Great Trilithon; specifically the upper part of the broken upright 55 (segment 55b) and lintel 156 (Fig. 2). Its shape was revealed during excavations in 1958 when the surrounding earth was removed (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). Based on the bevelled southeast end of the stone, Atkinson [1] concluded that it likely originally stood upright, though it also had features suggesting it may have lain flat. More recent sources, such as Pitts [2] and Parker Pearson [3], also mention both possible positions. The latter also refers to a possible stone hole but notes that its depth appears insufficient for foundation.

Fig. 3 Foot of the Altar Stone, upright 55b and part of the lintel 156, looking from NE, ©Historic England archive, please click here.

Fig. 4 SE end of the Altar Stone and it‘s sudden fracture, the fallen upright 55b and lintel 156, looking from E, ©Historic England archive, please click here.

Fig. 5 SE end of the Altar Stone, looking from NW, ©Historic England archive, please click here.

As far back as historical memory, illustrations and photos go, the Altar Stone has lain flat. In one of the earliest depictions—Stukeley’s drawing from the early 18th century—it even appears as if one could sit on it (Fig. 6). However, upon closer inspection, this image raises several doubts. Although the author does not know the exact dimensions of the stones lying on the Altar Stone, it can be estimated that the height of the fallen lintel’s edge is about 1 meter and the thickness of the broken head of upright 55 is about 0.7 meters. Given those dimensions, it is clear that the people depicted do not correspond proportionally to the stones and were likely added later. Based on the stone dimensions, the surface of the Altar Stone would have been about 15 cm above the ground, so the seated figure is more likely imaginative than realistic. Given the stated thickness of the Altar Stone—0.5 meters [1]—it had already been largely pressed into the ground by the weight of stones 156 and 55b lying on it. This suggests they fell long ago.

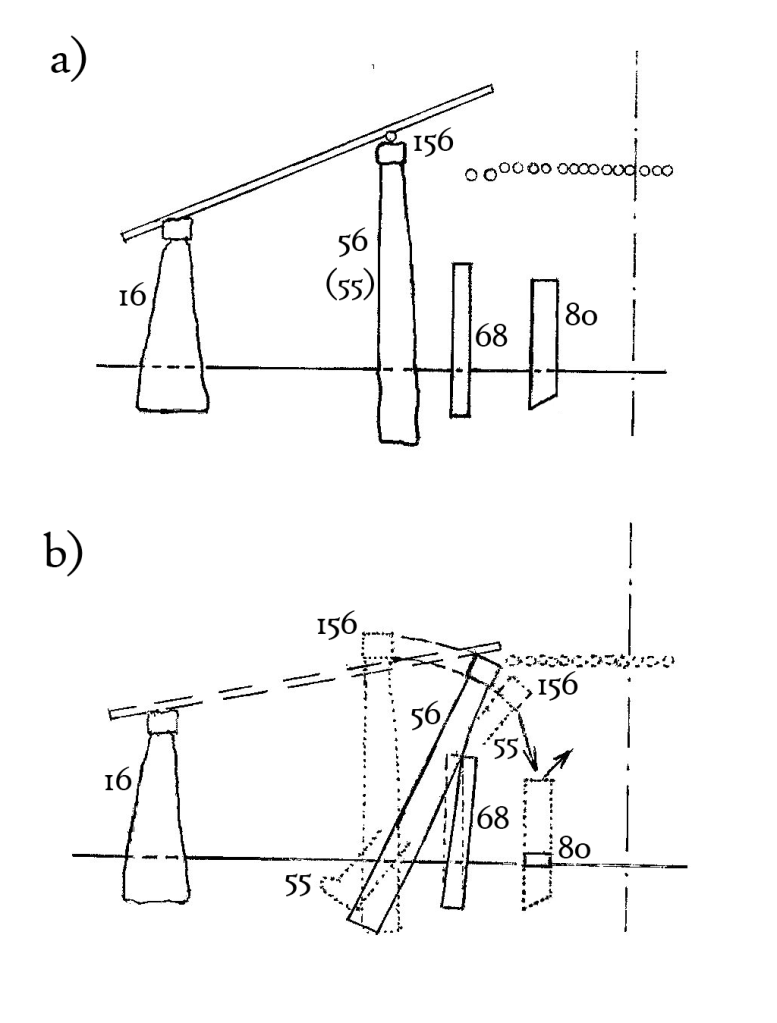

Structural analysis of the Stonehenge ruins and a reconstruction of its roof [4] have shown that the Great Trilithon was a supporting structure for the skylight roof (Figs. 7, 8). The prevailing wind’s force on the roof’s sloped surface gradually caused the Great Trilithon to tilt inward toward the center of the monument. This led not only to damage to the roof skylight, but also to the eventual partial collapse of the Great Trilithon, leaving upright 56 permanently tilted (Fig. 9). Early historical drawings from the late 16th century confirm this and align with the current position. It is therefore assumed that, despite earlier excavations and the temporary lifting of stones, the fallen parts of the Great Trilithon remain in their original positions. Only upright 56 was re-erected in the early 20th century.

Upright 56 leaned against pillar 68, deviating approximately 26° from the vertical. It is assumed that, even in this position, the large tenons on the uprights still held the lintel in place. While upright 56 remained largely in that position, nothing prevented the tilt of the neighbouring upright 55, which gradually increased over time (Fig. 10). As a result, the height difference between the two supports for lintel 156 increased, causing its southeast end to drop and fall first. Since both uprights were connected by the lintel, upright 55 also tilted diagonally. This is evident in its final slanted position after the fall, relative to the monument’s axis (Fig. 1). Ultimately, the extreme tilt caused upright 55 to lose stability due to its failed foundations (Fig. 11), resulting in its fall and simultaneous destruction of pillars 66 and 67. The impact broke it and also fractured the fallen Altar Stone (Figs. 3, 4). The nature of the breakage and the displacement of its broken parts suggest that the upright fell suddenly.

From the position of the fallen lintel 156 next to the base of upright 56, it can be inferred that something blocked its vertical fall from both uprights. That “something” could only have been a standing Altar Stone. Had it not been there, the lintel would have fallen more or less perpendicular to the monument’s axis. However, an impact from above and from the southeast redirected its fall next to the upper part of the fallen upright 55b and simultaneously knocked over the standing Altar Stone into its current lying position. The position of lintel 156 thus proves that, at the moment it fell, the Altar Stone was still standing, and therefore was originally an upright element. It only fell during the destruction of the Great Trilithon. It is also likely that, in keeping with the chosen astronomical orientation of the monument, the Altar Stone was installed already during the initial phase of the monument’s construction.

Analysis of the Great Trilithon collapse confirms Atkinson’s hypothesis that the Altar Stone originally stood upright. Moreover, if it stood along the monument’s axis, which is very likely, sunlight during both solstices would have fallen upon it. This would highlight the astronomical function of the structure—marking the solstice days. Therefore, the standing position of the Altar Stone may have indicated not only its own function but also the purpose of Stonehenge’s central structure [4]. The name Altar Stone should therefore perhaps be reconsidered—possibly renamed the “Solstice Stone.” To confirm this conclusion, further investigation should seek signs of damage to the northwest end of the Altar Stone caused by the impact of lintel 156, as well as the assumed location and shape of the Altar Stone’s original stone hole.

In article [3], in the context of the search for the Altar Stone’s original source, there is a hypothesis that the Stonehenge monument represents a symbolic unification of the whole island—though without specifying what kind of unification is meant. This hypothesis is based on the use of different types of stones sourced from various distances, the practically identical house types found in the distant Orkney Islands and in the Durrington Walls settlement near Stonehenge, as well as similarities between Scottish stone circles and parts of Stonehenge.

However, as shown in the above analysis of its position, the Altar Stone initially stood, and therefore its placement in the southwestern arc of the Sarsen Horseshoe group relative to the two pillars of the Great Trilithon would not have evoked any arc-like resemblance to the recumbent stone circles of northeastern Scotland. After the collapse of the Great Trilithon, when the Altar Stone became a fallen element, its immediate surroundings became an unclear and unusable ruin.

The similarity of house types in Durrington Walls and the Orkney Islands is logical and reflects developmental stages in the construction of wall corners. These may have developed independently or through knowledge transfer. However, Stonehenge, with its massive sarsen stones, was a structurally different and developmentally older structure than buildings made from smaller quarry stones. The outer walls of older houses in the Durrington Walls settlement were made of wattle, and the continuity at the corners was achieved through their curved shape. Until suitable stone bonding techniques were developed, this curved corner shape persisted. The transition to rectangular corners likely only came with the understanding of appropriate stone bonding techniques.

The Altar Stone’s different material compared to the others, and the fact that it was the only one of its kind, logically implies a distinct purpose. It stood out not only in shape but also in colour, which its upright position would have further emphasized. Therefore, rather than symbolizing the unification of the island, it likely performed a functional role within the monument—most probably as a Solstice Stone. The fact that its precise origin remains unknown does not change this. Likewise, the other two stone types at Stonehenge were selected based on their intended function—sarsen for strength and durability, and bluestone for its colour. Both were sourced from multiple locations, depending on accessibility and extraction possibilities.

It is clear that during the construction of Stonehenge—and in the period that followed—there were active connections among communities across the entire island. Its builders appear to have had a solid understanding of the properties of various stone sources and the technologies required for working with them. This was made possible by the parallel development of relevant knowledge and the growing demand for new and more sophisticated forms of construction. As such, it is debatable whether we can speak of any true unification—be it architectural, cultural, or otherwise—or rather of a gradual evolution and transformation of individual structures over the course of several centuries during the Neolithic period.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Mr. Antony Johnson (Fig. 1), Allphoto.cz (Fig.2), Historic England (Figs. 3, 4 and 5) and Mr. Simon Banton (Fig. 11) for permission to use their photographs — without which this article would lack sufficient documentation. Thanks also to Mr. John Nicholson for his English translation and commentary, and to my daughter, Ms. Karla Hanzlová, for her help with the graphics.

The author would like to dedicate this article to English Heritage.

Bibliography:

[1] Johnson, A.: Solving Stonehenge, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London, 2008

[2] Pitts, M: How to build Stonehenge? Thames & Hudson Ltd, London, 2022

[3] Parker Pearson, M., Bevins, R., Bradley, R., Ixer, R., Perace, N., Richards, C: Stonehenge and its Altar Stone: the significance of distant stone sources, Archaeology International, 2024

[4] Hájek, F: Reimagining Stonehenge: The Roof Theory, Solving Stonehenge, www.stonehengeroof.com, 2025

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and shared under the same license.